I wanted to explore the relative importance people place on difference aspects of running, regardless of how important the really are. So here is a book-indexed trend for each of the terms "VO2max", "running economy", "neuromuscular training" and "lactate threshold".

NB: On an earlier version of this post I had entered "Vo2max" and found a different, erroneous, trend. All sorted out now.

The term "VO2max" has been steadily rising from the 1980s to the early 2000s, where we may or may not be witnessing an ultimate peak around 2005. Though much smaller in book frequency, both "lactate threshold" and "running economy" reached their maximum values in 2002 and have been edging downward. Meanwhile "neuromuscular training" has been growing slowly but steadily. Since as Ngrams only reaches to 2008, I searched Google trends for more recent (search-based) differences.

The trend for these four variables has been quite stable between 2005 to present, with VO2max beating out the others by a fair margin. Therefore I included barefoot running as a more dynamic variable (NB: the phrase 'barefoot running' is quite flat during the pre-2009 ngram timespan). It is interesting to observe the sudden jump in barefoot searches in 2009, followed by a steep decline in 2014 to levels below those of VO2max.

Saturday, 6 December 2014

Saturday, 15 November 2014

Entering the sub 2-hour marathon debate

Background

The two-hour marathon: Can it happen? The debate heated up with Dennis Kimetto's time of 2:02:57 in the fall of 2014. As I recall, he was less than a kilometer from the finish when he crossed the two-hour mark. But even before Kimetto's run, Alex Hutchinson had already assembled a discussion on what it would take to run a sub 2-hour marathon.

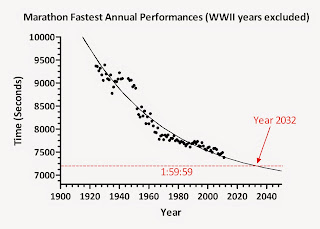

I have been watching these debates mainly from the sidelines as I hadn't found the data convincing enough either way. The only truly convincing (though most difficult) demonstration would be to run a 1:59:59 marathon. The easiest -and most problematic- line of reasoning is to plot marathon record time vs date achieved and extrapolate to one's peril:

This approach is much less unappealing, introducing no additional understanding of physiology or innate performance ability. Such extrapolations would never have predicted advances in the high jump, swimming, or speed skating. The curve itself is also a questionable line-of-best-fit.

The two-hour marathon: Can it happen? The debate heated up with Dennis Kimetto's time of 2:02:57 in the fall of 2014. As I recall, he was less than a kilometer from the finish when he crossed the two-hour mark. But even before Kimetto's run, Alex Hutchinson had already assembled a discussion on what it would take to run a sub 2-hour marathon.

I have been watching these debates mainly from the sidelines as I hadn't found the data convincing enough either way. The only truly convincing (though most difficult) demonstration would be to run a 1:59:59 marathon. The easiest -and most problematic- line of reasoning is to plot marathon record time vs date achieved and extrapolate to one's peril:

|

| Image from SweatScience's post 2032: Year of the Sub-2:00 Marathon? |

Tuesday, 11 November 2014

Qualifying times

A 2009 New york times article asked whether slow runners were spoiling the prestige of the marathon.

Many of those slower runners, claiming that late is better than never, receive a finisher’s medal just like every other participant. Having traversed the same route as the fleeter-footed runners — perhaps in twice the amount of time — they get to call themselves marathoners.If you are one of those going crazy, what to do? In order to surround yourself with fast(er) people, there is at least one option: the Boston Marathon. With its aged-based minimum entry standards, there is a certain density of speed not found in many races. Because Boston marathons have to already have run a marathon, a huge number of feeder races contribute to would-be pilgrims looking to qualify. It's a reasonably symbiotic relationship since many races can advertise their BQ potential. Yet it still leaves Boston's entry policy as popular yet unique. What other races do likewise? I googled "What marathons do you have to qualify for?". Here's what I found:

And it’s driving some hard-core runners crazy.

Tuesday, 28 October 2014

Oil!

CBC April 2012 article [Brent oil @ 120$/barrel]:

""The increase in the price of our oil imports raises production costs for Canadian firms and also puts upward pressure on gasoline prices, since about half of the gasoline purchased in Canada is produced using refined petroleum priced off Brent...That puts downward pressure on Canada's real gross domestic income, dropping the country's spending power to buy foreign goods and services"

CBC October 2014 article [Brent oil @ $85/barrel, and dropping]:

"On the whole, it's likely to be bad news for Canada's economy", experts said Monday..."The slump in global oil prices couldn't have come at a worse time for Canada...For a country that now produces 4.5 million barrels of crude oil per day, the recent decline in prices …represents a loss of $2.5 billion in annual revenue for producers"Expensive oil is bad since we aren't the ones refining it (and it seems we're in no position to build our own refineries). Cheap oil is bad since we can't sell Alberta's stuff at profit. As long as oil trades at exactly 100$ we're ok, just like Russia. I don't pretend to understand economies like ours, but sometimes there are moments that seem to defy all logic. Either way it seems we got ourselves some Dutch disease. Here we come!

Monday, 20 October 2014

Marathons and aging

What's the best age to run a marathon? There are a surprising number of pet theories floating around, anything from young runners are taking over the marathon to older runners are becoming more dominant. To quote from Runner's World:

Kenya's Samuel Wanjiru, 21, broke more than an Olympic record with his 2:06:32 win; he crushed long–held conventional wisdom that marathon performance peaks among runners in their late 20s and early 30s. That conventional wisdom also took a beating when a 38–year–old mother with 10 marathons under her belt, Romania's Constantina Tomescu–Dita, won the women's event.If conventional wisdom is being upended, i.e. that the age bracket of late 20s-to-early 30s are no longer when runners do their best work, it seemed prudent to find out what the numbers themselves say. Hence I compiled the men's and women's ~2400 fastest marathon times (including repeat performances by individuals) to asses whether there is any temporal trends for fast runners. I chose an arbitrary cutoff point to compare: the 20th and 21st centuries.

|

| Quote from here. Top Race times from here. Mean age for 1967-2000 group is 28.4. Mean age for 2001-2014 group is 28.3 |

Sunday, 12 October 2014

Joggling and other things

In no time at all I've seen September come and go. Mind you this was the month I had prepared for months in advance. Four things had to happen in two weeks, none of which were related. But thanks to a series of connecting, non-delayed flights, the segments of my trip fit together like square pegs jammed repeatedly, stubbornly through round holes.

Taking back a step, in the winter of 2014 I had originally planned that one of two things would happen come september: A. Race the 10k Toronto Zoo run (paid in part by winning the Nova Scotia running series) or B, attend the IGAC conference in Natal, Brazil. Seemed at the time I wouldn't do both. But things happen you don't expect.

Taking back a step, in the winter of 2014 I had originally planned that one of two things would happen come september: A. Race the 10k Toronto Zoo run (paid in part by winning the Nova Scotia running series) or B, attend the IGAC conference in Natal, Brazil. Seemed at the time I wouldn't do both. But things happen you don't expect.

|

| Email #1, April. Yay! |

|

| Email #2, August. Yay! |

Saturday, 6 September 2014

Mental Paella

What happens when you wait too long between entries? A backlog of all kinds of dumb, frivolous, unfiltered ideas that need expunging. Get out of my head, thoughts.

As personal penance, I'm retroactively listing 31 observations for the month of August.

1. Experimenting with my phone's "memo" function for writing notes while I have an idea. Not technically an app, per so. I don't have roaming-based functions for a simple reason: what percentage of my time do I honestly spend outside of free wifi zones? Home: wifi, work: wifi. Running: don't need internet. Walking: rater be thinking. Downtown Dhaka: probably don't have coverage anyhow. [I wonder what percentage of apps are made for single people? ]

Saturday, 9 August 2014

Canadians are slow

I was browsing this year's half marathon standings over at Marathon Canada.

The top ten include familiar names like Eric, Reid, Dylan, Kip, and Rob, much of the same crew that appeared in the top ranks in 2013.

While browsing the current results, the record-setting half marathon time of Florence Kiplagat came to mind; her run of 1:05:12 is faster than all but six Canadian men runners in 2014 (so far) and 2013.

At first glance this seems rather disappointing with respect to the canadian men with so few athletes running anywhere near their potential.

But is it fair to compare the men's time with a world record female run? Consider the CIS standard for the 1000m, which for men is just under 2:25. For those unfamiliar, running below this time automatically qualifies any athlete for the finals. Usually a half dozen or so athlete manage the feat in any given year. But the women's world record time for the same event is just under 2:29 (set by Svetlana Masterova, a non-Kenyan much to my surprise). In other words a National University-level performance for men is 2.8% faster than the world's best female time.

Were the half marathon to be judged by the same criteria (of being ~2.8% faster than the female WR), we might expect a certain number of male Canadian runners to achieve times better than 63:30.

As it happens the fastest 2014 Canadian male time for the half is 63:30. Over the past six years between 1 and 4 athletes have run faster than this time.

If it seems as though I'm picking on the half marathon, consider the same criteria applied to the marathon make matters worse: With Paula Radcliffe's time of 2:15:25 and using the same 2.8% yields 2:11:43. Between zero and two Canadian men achieve this standard each year.

Now keep in mind that men, compared to women, generally get faster as distances get longer (ignore what you may have read in Born to Run). The fact there fewer male runners capable of a "quality" road time that's routinely achieved on the track is troubling.

There are many hypotheses to explain this away. My observation is that Canada is too insulated in the world of road racing. Too many road races and not enough athletes means everyone can win a race without having to truly 'compete'.

By contrast the CIS university circuit is artificially constrained and condensed, which perhaps encourages faster times with the top performers comparing each to the other. The road racing talent is there, but more dilute, and it seems possible Canada -being a large country- is below some competitive critical mass.

I had an idea the other week about a series of road races that had time bonuses, and ONLY time bonuses, as prize money. You still get to stand on the podium if you win, but the money is entirely from how fast you run. I know, every road course is different so sometime it wouldn't work. But the idea is to stimulate the same results as seen in the CIS. There must be ways of improving the top performances among our best, for they can do better.

The top ten include familiar names like Eric, Reid, Dylan, Kip, and Rob, much of the same crew that appeared in the top ranks in 2013.

While browsing the current results, the record-setting half marathon time of Florence Kiplagat came to mind; her run of 1:05:12 is faster than all but six Canadian men runners in 2014 (so far) and 2013.

At first glance this seems rather disappointing with respect to the canadian men with so few athletes running anywhere near their potential.

But is it fair to compare the men's time with a world record female run? Consider the CIS standard for the 1000m, which for men is just under 2:25. For those unfamiliar, running below this time automatically qualifies any athlete for the finals. Usually a half dozen or so athlete manage the feat in any given year. But the women's world record time for the same event is just under 2:29 (set by Svetlana Masterova, a non-Kenyan much to my surprise). In other words a National University-level performance for men is 2.8% faster than the world's best female time.

Were the half marathon to be judged by the same criteria (of being ~2.8% faster than the female WR), we might expect a certain number of male Canadian runners to achieve times better than 63:30.

As it happens the fastest 2014 Canadian male time for the half is 63:30. Over the past six years between 1 and 4 athletes have run faster than this time.

If it seems as though I'm picking on the half marathon, consider the same criteria applied to the marathon make matters worse: With Paula Radcliffe's time of 2:15:25 and using the same 2.8% yields 2:11:43. Between zero and two Canadian men achieve this standard each year.

Now keep in mind that men, compared to women, generally get faster as distances get longer (ignore what you may have read in Born to Run). The fact there fewer male runners capable of a "quality" road time that's routinely achieved on the track is troubling.

There are many hypotheses to explain this away. My observation is that Canada is too insulated in the world of road racing. Too many road races and not enough athletes means everyone can win a race without having to truly 'compete'.

By contrast the CIS university circuit is artificially constrained and condensed, which perhaps encourages faster times with the top performers comparing each to the other. The road racing talent is there, but more dilute, and it seems possible Canada -being a large country- is below some competitive critical mass.

I had an idea the other week about a series of road races that had time bonuses, and ONLY time bonuses, as prize money. You still get to stand on the podium if you win, but the money is entirely from how fast you run. I know, every road course is different so sometime it wouldn't work. But the idea is to stimulate the same results as seen in the CIS. There must be ways of improving the top performances among our best, for they can do better.

Monday, 4 August 2014

Work and exercise

As I sit leisurely on my couch at home, I am reading an NPR piece titled What Makes Us Fat. The argument goes (until the next study comes out) that physical activity has been going down faster than potion sizes have been going up.

That very well might be true. Part of the support for this line of reason is that work-related energy expenditures have been going steadily down. To quote the NPR piece:

That very well might be true. Part of the support for this line of reason is that work-related energy expenditures have been going steadily down. To quote the NPR piece:

[Dr.] Church took the findings one step further and calculated how many calories were no longer being burned. He found it was about 140 fewer calories burned a day for men and 120 fewer calories burned a day for women. "That doesn't sound like much, but when it's day after day after day, it adds up," he says.I found data agreeing with this claim. Dr. Joyner, in a piece titled How the USA Got So Fat incorporated the same data from Church's paper on his own blog:

Thursday, 24 July 2014

Not that skinny

Below this is me, my BMI that is. The entire range in which it's existed since the last 10 years.

My height is 5'11", weight ranges between 140 and 155 lbs. I used to weigh about 160 lbs before I ran as much as now, losing about 10 lbs in the process. Now as someone who runs regularly, that's supposed to mean I'm a skinny person. But really I'm not skinny in any clinical sense, just a tiny bit below the absolute middle of the "Normal" range.

But I can understand the misinterpretation. Six in 10 Canadians are well above that mark, so it makes sense standing next to most anyone I look skinny. It's entirely an illusion.

There are underweight runners, but they're easy to spot, and they lose races. Pretty much all track and field athletes are in a rather normal weight range. Don't anyone be afraid they'll get "too skinny" while running.

Sunday, 20 July 2014

Multi-cycle training: outline of a possibly-new training method

It's about time I pin down the thoughts circling in my head over the past few weeks. I've made analogies about how to perceive running training. A fugue was one, arches another. But these are merely analogies to something that I haven't yet fully described. Here and now I will outline a meta training scheme that may -or may not- be useful. My only claim is that I have not seen it before, hence it could be worth considering.

If you'd like to skip ahead, in a few paragraphs I will describe how overlapping different cycles for different training elements could lead to possible added stimuli in a training plan without a strict need to "up the mileage". Just look for the *****text and asterisks in bold*****.

If you are interested in reading the early stuff, let's outline what these training elements are.

If you'd like to skip ahead, in a few paragraphs I will describe how overlapping different cycles for different training elements could lead to possible added stimuli in a training plan without a strict need to "up the mileage". Just look for the *****text and asterisks in bold*****.

If you are interested in reading the early stuff, let's outline what these training elements are.

Saturday, 21 June 2014

Too many notes

Most runners don't see the sheer possibilities inside a training schedule.

Consider a weekly training block, one which the runner is going about 80 miles per week. This leaves plenty of room to play. Here's a theoretical week for such a runner broken into mornings and evenings:

You can see the running is semi-distributed, with chunks of big miles followed by rest days. But let's change things a little, moving miles here and there, and modifying workouts a little to spread the miles even more:

And again let's return to lumpier mileage, but still different from the first:

Or for that matter let's try having only single-run days

Consider a weekly training block, one which the runner is going about 80 miles per week. This leaves plenty of room to play. Here's a theoretical week for such a runner broken into mornings and evenings:

You can see the running is semi-distributed, with chunks of big miles followed by rest days. But let's change things a little, moving miles here and there, and modifying workouts a little to spread the miles even more:

And again let's return to lumpier mileage, but still different from the first:

Or for that matter let's try having only single-run days

Sunday, 15 June 2014

Cortisone injections in athletes

It is a well-known fact that many injured athletes get cortisone shots when joint inflammation becomes too painful to play (translation: I'm too lazy to provide a bunch of references).

What's less well-known is that repeated injections lead to no good. Clearly inflammation occurs in joints and other parts of our body for good reason. Except for critical cases like swelling of the brain, one should hesitate alleviating such inflammation, which usually is a sign of bodily repair underway. It's important to know exactly what you're doing and why.

The following two papers are concerning back pain but this is as good a place to start as any since back pain can be crippling, hence the solutions sought provide immediate relief. Let's combine the quest of athletes and back pain in one fell swoop. Browsing Google Scholar I came across an old-ish (1980) paper that stated

Thirty-two young athletes (ages ranging from 17 to 30 years) with a clinical diagnosis of a symptomatic lumbar disc and sciatica [read: back pain] were treated with lumbar epidural cortisone injections. All had had disabling symptoms persisting for a minimum of 2 weeks, with an average duration of 3.6 months. Dramatic abatement of symptoms and a significantly hastened return to competition (a positive response) was seen in 14 (44%) of the 32 athletes following injection.

Tuesday, 3 June 2014

Weekly training

Though I'd start a weekly training log. I haven't done one in a while. Problem is I don't really write down the miles I run. So here goes

Monday: Might have take this day off. Can't remember. I dunno.

Tuesday: Think I ran twice this time. Once in morning, once in evening. The second time I did some intervals. Was it 5x800m in 2:20-something? Probably.

Wednesday: Guess I ran for an hour. Sound about right.

Thursday: More running. Nine or ten by 200m. Didn't bring a watch so no idea how fast they were. Felt nice though.

Friday: Some pool and regular running.

Saturday: Ran a 5k in 15:30. Didn't feel very fast. Would someday like to do one in 14:30.

Sunday: Two hours, more or less. Didn't time it exactly. How many miles? Don't care.

That's all! I imagine other weeks will be the same, so I won't do this again. TTFN.

Monday: Might have take this day off. Can't remember. I dunno.

Tuesday: Think I ran twice this time. Once in morning, once in evening. The second time I did some intervals. Was it 5x800m in 2:20-something? Probably.

Wednesday: Guess I ran for an hour. Sound about right.

Thursday: More running. Nine or ten by 200m. Didn't bring a watch so no idea how fast they were. Felt nice though.

Friday: Some pool and regular running.

Saturday: Ran a 5k in 15:30. Didn't feel very fast. Would someday like to do one in 14:30.

Sunday: Two hours, more or less. Didn't time it exactly. How many miles? Don't care.

That's all! I imagine other weeks will be the same, so I won't do this again. TTFN.

Saturday, 24 May 2014

Hey, I won a race (and other observations)

So I won the Halifax bluenose half marathon and got a new PB of 1:09:44. This is not the fastest time in world, I know, but the race felt great, I knew lots of people on and off course, and surprised a few co-workers that didn't know I was racing (or that I did any road races period). I guess what got people talking was that I beat one of three visiting Kenyans. The other two set course records (2:36 and 2:27, respectively) but these were slow times compared to their personal bests because the course was hilly. Knowing that, plus runner-up Ewoi's half PB of 1:07 some years ago gave me added satisfaction that my sub 70 was not a fluke.

Why were Kenyans at the Bluenose race? It's an interesting story since BN does not give out prize money. Usually money is the only reason an elite runner comes to any non-hometown race. In this case Ethan Michaels brought the trio to Canada on his own dime, having travelled to Kenya on numerous occasions for, what I understand have been, running-themed vacations.

|

| Me at the finish line |

Saturday, 10 May 2014

Tidbits and updates and thoughts of stuff

Where does the time go? I was surprised to realize my last post was in March, not April. This when I'm supposed to say I've been busy with other things blah blah, but truth be told there were plenty of chances to sit down and write.

I have the curious habit of not writing about the thing I do while doing it. For instance during April and early May I ran three races and did a lot more actual training intervals, tempo, strength. Next week I'll run in the Bluenose half marathon. It may go well, or not. I cannot say.

The past, however, is safely behind me so I can talk about that. The training went well, hence so did the races. In the last two weeks I had the good fortune to set two bests. April 27th was a trip to Montreal for a half marathon, running in 70:15, beating my 2008 time of 70:27. Last week I ran 15:15, which beat my old 2009 time of 15:27. Neither are huge improvements, but significantly (to me, at least) they were done on few, if any, intervals. They were build on a foundation of tempo, strength, and easy stuff. I have learned a ton about training since my mid 20s. And perhaps equally as important I've learned to unlearn things, namely that a massive warmup routine is mostly BS, strides are overrated, intervals are best used in very small quantities (imagine them as a powerful spice), and finally run easy. If I could go back in time to days I ran 'easy' while still keeping my 7min/mi pace I'd tackle me to the ground while yelling 'slow the f*** down'.

The past, however, is safely behind me so I can talk about that. The training went well, hence so did the races. In the last two weeks I had the good fortune to set two bests. April 27th was a trip to Montreal for a half marathon, running in 70:15, beating my 2008 time of 70:27. Last week I ran 15:15, which beat my old 2009 time of 15:27. Neither are huge improvements, but significantly (to me, at least) they were done on few, if any, intervals. They were build on a foundation of tempo, strength, and easy stuff. I have learned a ton about training since my mid 20s. And perhaps equally as important I've learned to unlearn things, namely that a massive warmup routine is mostly BS, strides are overrated, intervals are best used in very small quantities (imagine them as a powerful spice), and finally run easy. If I could go back in time to days I ran 'easy' while still keeping my 7min/mi pace I'd tackle me to the ground while yelling 'slow the f*** down'.

Saturday, 22 March 2014

Arches: a new conceptual model for running

I don't like pyramid models. Although a well-built pyramid certainly looks nice, they rarely provide a good model for a healthy system. Think Ponzi schemes: a strict hierarchy where only the topmost members benefit. Pyramids are a great analogy for dictatorships, kingdoms, or the catholic church. None of these things are something you'd aspire to mimic for a system that benefits most through cooperation.

Before I get to running, consider one other bad pyramid model: food. For some reason pyramids are used in nutrition. The food pyramid clearly makes no sense. How is it that vegetables are supporting fish and oils, and not the other way around? Why are eggs and sweets near the top? What if you are vegetarian? Do you want to place the most important food items on top, or the least? Why are calorie-rich foods scattered so randomly? For any practical purposes the food pyramid is confusing. More to the point it's just a bad model for something so intricate.

Sunday, 23 February 2014

Which country 'won' Sochi?

There's always some debate about how to rank the medal tally of all the countries. Some news outlets rank by number of gold. The second option is to tally the total bronze, silver, and gold. CBC chose to rank by pure gold, which puts Canada in third and USA fourth, while NBC took the total count, which places USA second and Canada fourth. Hmmm. How about we try a points system, where Gold = 3 points, Silver = 2, and Bronze = 1. This takes a middle ground where runner-up performances still count while admitting gold ought to be worth more than bronze. In this case here's the Sochi 2014 medal table:

Russia is the clear winner with 70 points, while Canada's 55 points edges out Norway and the United States who are tied third with 53. The overall rankings are only tweaked a little, which is good not to upset the apple cart entirely. One modification I could suggest is to count team sports for more points since it's impossible for a given country to sweep the medals (i.e. Canada's men's hockey team can win at most one gold while the Netherlands can, and have, won multiple medals per event). Then again sweeping the podium is an equal opportunity event hence I'm not going to change the table.

I forgot to mention a third way people rank the olympics, which is dividing that countries' population by the metal count to 'normalize' the rankings. You could do that here too, but with points instead of using the (oversimplified) medal count. Here's the rankings again with a points per capita:

No surprise that Norway is the clear winner with 10.3 points per million people; on average every 100,000, or a tiny city in Norway, generates an Olympic point. Slovenia and Switzerland rank in second and third, which I would not have considered intuitive choices. Meanwhile Canada and Russia slip all the way down to ninth and 14th, respectively (I kept the original rank numeration so you can see how much shifting there is). No surprise that China sits in dead last for winter, but maybe if we tried doing this with London 2012 something interesting could emerge. But that's for another post.

Russia is the clear winner with 70 points, while Canada's 55 points edges out Norway and the United States who are tied third with 53. The overall rankings are only tweaked a little, which is good not to upset the apple cart entirely. One modification I could suggest is to count team sports for more points since it's impossible for a given country to sweep the medals (i.e. Canada's men's hockey team can win at most one gold while the Netherlands can, and have, won multiple medals per event). Then again sweeping the podium is an equal opportunity event hence I'm not going to change the table.

I forgot to mention a third way people rank the olympics, which is dividing that countries' population by the metal count to 'normalize' the rankings. You could do that here too, but with points instead of using the (oversimplified) medal count. Here's the rankings again with a points per capita:

Sunday, 16 February 2014

Olympic gold and cash

I came across an info graphic from CBC about which countries pay money for winning Olympic medals.

My first reaction was there wasn't much correlation between either how many medals the country actually won and how much the athlete got paid for gold. Nor is it clear how much these athletes get paid, if anything, when not winning gold. Most likely the wealthier countries pay their athletes some stipend when training. Then again, poorer countries may have elite training programs, assuming you qualify for one such as Russia's Red Army.

Nevertheless, since winning gold is rarely, if ever, a reliable source of income I figured these cash prizes were a form of saving face for the countries themselves and less so for rewarding athletes. It's as if to say "look, we don't shortchange our athletes, at least if they are winning". I wondered if there was a correlation between the prize money and the general wealth of these countries per capita. Hence I took the figure 1 prize values and plotted them against GDP.

The correlation is not perfect, but the results are relatively clear: poorer countries give relatively more money to the winning athletes than richer ones. My guess is that these athletes make little money and to avoid the embarrassment of having a gold medalist living in poverty, it would be wiser from a publicity point of view to reward them enough to live comfortably in future years, or at least until they are forgotten.

There is a deeper significance to the negative correlation in figure 2. Wealthier countries can potentially afford larger medal prizes than poorer ones. And poorer countries don't win enough medals for these payouts to be a significant cash drain. Hence the absolute money given out to athletes is rather arbitrary. Canada pays out $20,000 per gold medal. This is a pittance when you consider the years of effort required to earn one. An annual graduate stipend in a canadian science program is more than 20 grand, which is also small, and there are a lot more graduate students than Olympics athletes in Canada. The majority of legitimate money comes from sponsorship deals like commercials and public appearances for talks. Is this a good point in favour of capitalism in amateur sports? I need to look into this a little deeper.

|

| Figure 1. From CBC website |

Nevertheless, since winning gold is rarely, if ever, a reliable source of income I figured these cash prizes were a form of saving face for the countries themselves and less so for rewarding athletes. It's as if to say "look, we don't shortchange our athletes, at least if they are winning". I wondered if there was a correlation between the prize money and the general wealth of these countries per capita. Hence I took the figure 1 prize values and plotted them against GDP.

|

| Figure 2: Olympic prize money compared with GDP per capita wealth per country |

There is a deeper significance to the negative correlation in figure 2. Wealthier countries can potentially afford larger medal prizes than poorer ones. And poorer countries don't win enough medals for these payouts to be a significant cash drain. Hence the absolute money given out to athletes is rather arbitrary. Canada pays out $20,000 per gold medal. This is a pittance when you consider the years of effort required to earn one. An annual graduate stipend in a canadian science program is more than 20 grand, which is also small, and there are a lot more graduate students than Olympics athletes in Canada. The majority of legitimate money comes from sponsorship deals like commercials and public appearances for talks. Is this a good point in favour of capitalism in amateur sports? I need to look into this a little deeper.

Thursday, 30 January 2014

Trail running and brain training

|

| Trail running. Image from here. |

I was asked to maybe write something about "trail running and the brain", so I gave it a shot. Here's the article, more or less how it may appear in a few months time.

----

Some runners might avoid trail running due to a (legitimate) concern over twisted ankles. Others stay on the roads because this is where GPS watches -and similar devices- are useful for pace and distance. By contrast, there is no way to interpret what several miles of rugged terrain mean either in terms of speed or mileage. Perhaps one mile up a mountain is worth five on a treadmill. What does running an "even pace" mean on trails? My first mountain race was two laps around a ski hill, and despite never doing such a thing before I kept a constant effort for most of the race. Somehow the body knows. Growing up I had never given much thought to precise pacing in cross country (be it skiing or running); whatever the speed, it always felt instinctively right.

Sunday, 19 January 2014

Optimal speed on an indoor track

Consider yourself running on an indoor running track surface. The turn has a banked incline, which ostensibly helps making fast turns easier. How fast does one need to run around a banked curve to balance the forces of gravity and centripetal motion?

When running slow, say a light jog, a banked turn can feel awkward (you feel yourself being pulled off the track). Run too fast and you'll feel a pull outwards (though less than if there was no bank at all.)

The following diagram outlines the physics involved.

The specific forces we wish to balance are gravity and centripetal, at angle theta:

Assuming no friction, the velocity v for angle theta and radius r is

The IAAF gives a detailed plan for building an indoor 200m track here. Curves are banked at 10 degrees (18% grade) and the internal radius r = 17.5 m. Each additional lane (e.g. 2, 3..6) adds an extra 0.9 meters to the total curved radius.

The optimal speed v for the first lane of a track is therefore 5.5 m/s, or 19.8 km/h. The optical speed for the 6th lane is 22.2 km/h. One should feel the most "balanced" racing a banked turn at approximately 20 km/h. To place this in perspective, a 10 minute 3000m race is 18 km/h; at 9 minute it is run at 20 km/h, and 8 minutes is 22.5 km/h. 20 km/h is around the speed of a competitive women's 1500m-3000m university race.

Of course one can run much faster than 20-something km/h on an actual course since cleated footwear is high in fractional forces. Friction, mu, prevents sideways movement hence adds to the maximum speed.

Assuming a static friction coefficient of mu = 1, you'd stay glued to a 10-degree banked surface up 15.6 m/s or 56 km/h, enough for even the fastest sprinter. What if we increased the banking? If mu = 0 (no friction) but banked at 45 degree like a Velodrome, you could run up to 13 m/s. The optimal speed for a given banking is given the table below:

If there is no banking at all (theta = 0) then all centripetal motion is countered with frictional forces. Assuming mu = 1, the maximum speed around a non-banked curve is 13.1 m/s, still fast enough to support any runner. Even a tiny flat track of radius r = 5 m could support a speed of 7 m/s (25 km/h), fast enough for a 3:36 1500m run. This is why we never see people fly off the outside of a track.

Returning to our official track of r = 17.5 and theta = 10 degree, then running the inside lane at 20 km/h, or 36 seconds a lap, is ideal if interested in minimizing sideways forces.

When running slow, say a light jog, a banked turn can feel awkward (you feel yourself being pulled off the track). Run too fast and you'll feel a pull outwards (though less than if there was no bank at all.)

The following diagram outlines the physics involved.

|

| Wikipedia diagram of a banked turn; balancing the forces. |

Assuming no friction, the velocity v for angle theta and radius r is

The IAAF gives a detailed plan for building an indoor 200m track here. Curves are banked at 10 degrees (18% grade) and the internal radius r = 17.5 m. Each additional lane (e.g. 2, 3..6) adds an extra 0.9 meters to the total curved radius.

The optimal speed v for the first lane of a track is therefore 5.5 m/s, or 19.8 km/h. The optical speed for the 6th lane is 22.2 km/h. One should feel the most "balanced" racing a banked turn at approximately 20 km/h. To place this in perspective, a 10 minute 3000m race is 18 km/h; at 9 minute it is run at 20 km/h, and 8 minutes is 22.5 km/h. 20 km/h is around the speed of a competitive women's 1500m-3000m university race.

Of course one can run much faster than 20-something km/h on an actual course since cleated footwear is high in fractional forces. Friction, mu, prevents sideways movement hence adds to the maximum speed.

Assuming a static friction coefficient of mu = 1, you'd stay glued to a 10-degree banked surface up 15.6 m/s or 56 km/h, enough for even the fastest sprinter. What if we increased the banking? If mu = 0 (no friction) but banked at 45 degree like a Velodrome, you could run up to 13 m/s. The optimal speed for a given banking is given the table below:

If there is no banking at all (theta = 0) then all centripetal motion is countered with frictional forces. Assuming mu = 1, the maximum speed around a non-banked curve is 13.1 m/s, still fast enough to support any runner. Even a tiny flat track of radius r = 5 m could support a speed of 7 m/s (25 km/h), fast enough for a 3:36 1500m run. This is why we never see people fly off the outside of a track.

Returning to our official track of r = 17.5 and theta = 10 degree, then running the inside lane at 20 km/h, or 36 seconds a lap, is ideal if interested in minimizing sideways forces.

Wednesday, 15 January 2014

Running strides part 2: Takeoff angles and other predictions

In Part 1 I showed that some basic predictions can be made about running contact times knowing only one's turnover rate R (cadence; steps per second) as a function of vx (your forward speed in m/s) and dleg (the length of your extended leg, in metres). The first assumption I made was that R can be expressed as a function of vx and Lleg. From the early figures in part 1, this looked to be roughly true. The second assumption was that the distance of your running step, dstep, which is the distance covered per stride was equal to Lleg and that this is true regardless of your running speed. To verify if these assumptions were indeed correct, I calculated the ground contact time (time spent on ground; GCT) and aerial time (time spent in air; AT) and compared them to actual empirical values.

Again, here are the two equations for GCT and AT, respectively:

I found my predictions were, within measurement error and natural human variation, equivalent to several published values. The next step is to then expand our horizons and make bolder predictions.

Again, here are the two equations for GCT and AT, respectively:

Sunday, 12 January 2014

Running strides Part 1: ground and aerial contact times

I'm going to break apart my discussion of running into two posts. This first post lays out the foundations of how to calculate certain elementary running metrics including time spend in the air per running stride and time spent on the ground. Consider this an expansion of my previous discussion on the short life of a foot strike. The second part will use the foundations here to predict some perhaps more original calculations for running, including stride angles and ground forces experienced by a runner. I am not claiming I've discovered any novel numbers per se, but maybe a new approach to obtaining them. That is to come later, however. For now let's consider some basic calculations, for even these results may surprise the curious (scientist) runner.

Turnover rates, R

Let's begin with running turnover rates, which are complex entities but with lots of empirical data to back them up. They are easy to measure but hard to predict. Empirically you just measure a runner's speed and count their strides per unit time. Theoretical turnover rates, which require knowledge of a runner's muscle system, surface stiffness, etc, are by contrast very difficult-to-predict entities.

Stride rate is defined here by R in steps per second. Running at 180 steps per minute translates to 3 steps per second. Alex Hutchinson has already disused in some detail the degree to which step rates increase with speed. Here is the a plot of his combining several running studies (and some self-reported numbers) on turnover rate. Note his plot show steps per second of a single leg, not both, hence the numbers are half of the total turnover (180 strides per minute is equivalent to 1.5 strides per second per leg). Here is Alex's combined data set for turnovers for various runners:

|

| Figure 1: Turnover rates at variable speeds |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)